Cheating at Chisholm

Staff, students, and surveys reflect the attitudes toward academic dishonesty across campus

Sitting at my desk during Physics in late April, my only emotion was annoyance. To prevent cheating, students were not allowed to take a ten-page packet home.

The thought was that students were less likely to cheat while in the room with their own teacher.

A cursory glance at the class could show the flaws in this idea however. While many students furiously worked through problems in the packet and tried their best to finish the labs by the due date, others simply passed their finished packets around in groups.

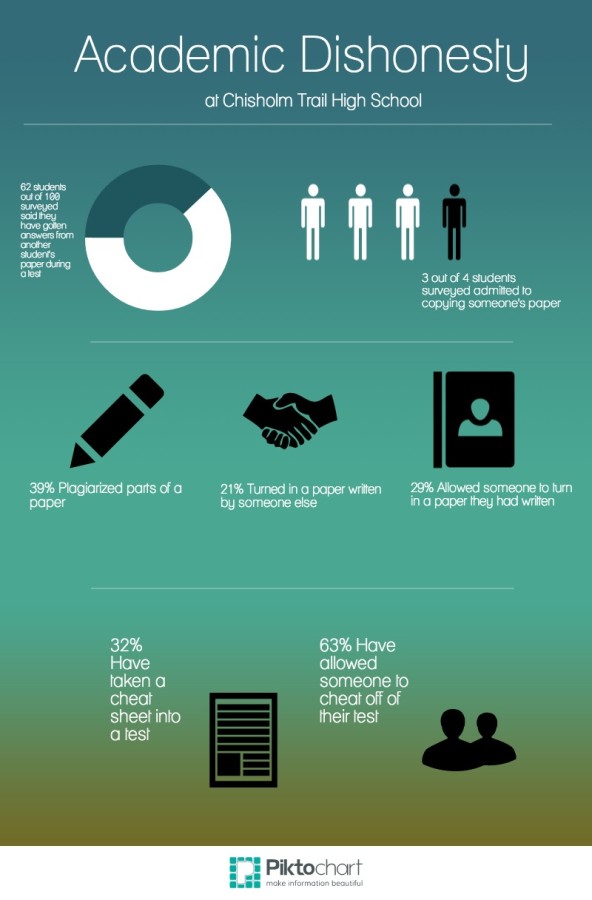

Rangers cheat like high school students across the country. Out of 100 students surveyed in May, three out of every four students admitted to copying someone’s paper. These numbers are similar to a survey conducted by the Josephson Institute Center for Youth Ethics where 59% of students admitted to cheating.

In January, students photographed the U.S. History and Physics exams and posted them to social media. Because teachers across the district use the same tests, students from all three high schools were impacted.

As the end of the semester comes to a close once again, the Cinco Peso Press decided to pursue the question: Do students cheat more now than they did in the past?

“Oh yes,” Spanish teacher Onelia Lobo-Guerrero said as soon as the question is asked.

“They’re so used to working together,” Lobo-Guerrero said.

Although Lobo-Guerrero started her teaching career a near five years after graduating from college, it was still a shock seeing how carelessly students cheated.

Kids had changed abruptly from her high school years. There were still the class clowns and the unmotivated, but there were also some new students.

There were the outspoken. There were the blunt. And they were all very codependent.

When she was in school, Lobo-Guerrero sat mostly in rows of desks. Now, most students sit in groups and work together on assignments. Despite the many benefits cooperative learning can have, Lobo-Guerrero does believe that this type of learning has led to more cheating.

“[Cooperative learning] teaches them not to be solely responsible,” Lobo-Guerrero said. “They don’t see the difference of hierarchy, of superiority.”

She foresees the problems students’ ease with cheating will cause for them in the future.

“When they go out and get a job, have a boss, they aren’t going to get all these ‘Oh you screwed up? Let me just slap your hand and give you another opportunity,’” she said.

Lobo-Guerrero has long since learned that reading out parts of the Student Handbook and listing the consequences is not enough to get students to avoid cheating.

The most damaging part of cheating in Lobo-Guerrero’s opinion however is the lack of learning student

“They don’t see the difference between an elective and an academic elective,” she said. “I’m not downplaying art or the arts or anything like that, but those are different expectations, different guidelines, different information that they’re going to use and apply.”

Although many students believe that the world is moving to become an English-speaking world, there is still room for foreign languages, Lobo-Guerrero said.

For those who find foreign languages challenging, Lobo-Guerrero’s advice is practice.

Putting at least a 20 percent effort into studying would improve many students’ grade significantly she believes.

However, Lobo-Guerrero doesn’t automatically demonize students who resort to cheating either.

“They just don’t want to be seen as failures.”

*************************************************************************************

“The opportunity has grown exponentially,” Principal Dr. Mike Schwei said of cheating while sitting in his office on a Friday afternoon.

He remembers proctoring a room during a state-mandated test many years ago. Test-takers were not allowed to wear hats out of fear of hidden cameras and video devices.

For Schwei, there is no such thing as a single incident of cheating.

“It affects their whole characters and personalities for the rest of their lives,” Schwei said of students who cheat. “I believe if you cheat once it becomes easier to cheat the second time and then the third time.”

Although Schwei agrees with Lobo-Guerrero that collaboration is an important skill in both school and in the workforce, he believes there comes a time when individuals need to prove their own personal knowledge.

For Schwei cheating is simple, it is any work submitted that is not a reflection of your own personal knowledge and skills.

Unlike Lobo-Guerrero though, Schwei believes that students 30 years ago were as likely to cheat as they are today.

The only difference between students today and from the past is that today’s students have more opportunities to cheat.

The January exam photo incident exemplifies the ease of cheating today. After the two semester exam answer keys were leaked on social media, an investigation was carried out to determine which students had cheated.

Schwei said the investigation turned up no hard numbers.

“Any junior that wanted to could have had access,” he said.

In the end, Schwei said cheating is a moral decision. He encourages students to do some soul-searching. To seek tutoring and teachers’ help. To question why they’re inclined to cheating.

He also wants students to consider the effects of their actions.

“Who are you cheating if you cheat?”

*************************************************************************************

For junior Emma George cheating is just like Schwei’s definition, any unoriginal work or idea.

But unlike Schwei and Lobo, George doesn’t see what the big problem is with cheating. “I think the amount of pressure put onto kids to come up with their own original ideas makes it hard not to want to cheat,” George says.

She has several theories on why students have trouble coming up with their own ideas. One theory is that in classes where the subject is more difficult or not taught very well, cheating is unavoidable.

“It’s harder for them to use their own ideas when there isn’t any [new ideas],” George said.

Another theory George has is that the way schools teach does not cater to all of students’ individual needs.

“I think if schools became less rigorous and focused more on an individual student’s ideas and how they want to learn then cheating would go down drastically,” George said.

Her final theory is that the standards schools hold students to are just too unattainable.

“The fact of the matter is we’re teaching people on a basis that nobody can really achieve so they have to cheat in order to get to that basis,” George said.

There are several punishments for cheating that as a student George views as ineffective.

-Punishing the whole class by having them redo the assignment

-Making the assignment not count towards anyone’s grades

-Having students redo the exact same paper.

The thing that upsets George most about cheating however is not the act itself but the way students who cheat are treated.

“People aren’t bad people because they cheat, it’s more or less the reason they’re cheating that makes them bad or good,” George said. “’Cheaters are all bad people’ or [the idea] that they need to be punished for cheating, that bothers me.”